Samuel Pepys: A modern man.

Here's an article I wrote recently for the English History Fiction Writers website. Enjoy.

Samuel Pepys: A man of our times.

On the 31st May, 1669, Samuels Pepys wrote in his diary, ‘And so I betake myself to that course, which is almost as much as to see myself go into my grave: for which, and all the discomforts that will accompany my being blind, the good God prepare me!’ It was to be the last entry. For the previous nine and a half years, he had been keeping the diary religiously, writing an account of his life and the world that surrounded him.

He was fortunate (or unfortunate) to live in an amazing time, witness to the great events that shaped Stuart Britain. He lived through a period of turmoil; the death of one king, the reign of a dictator, Oliver Cromwell, the restoration of the Monarchy under Charles II, the deposition of his brother, James II and the crowning of William of Orange, an outsider and king of a country which in 1667 had devastated the Navy he loved.

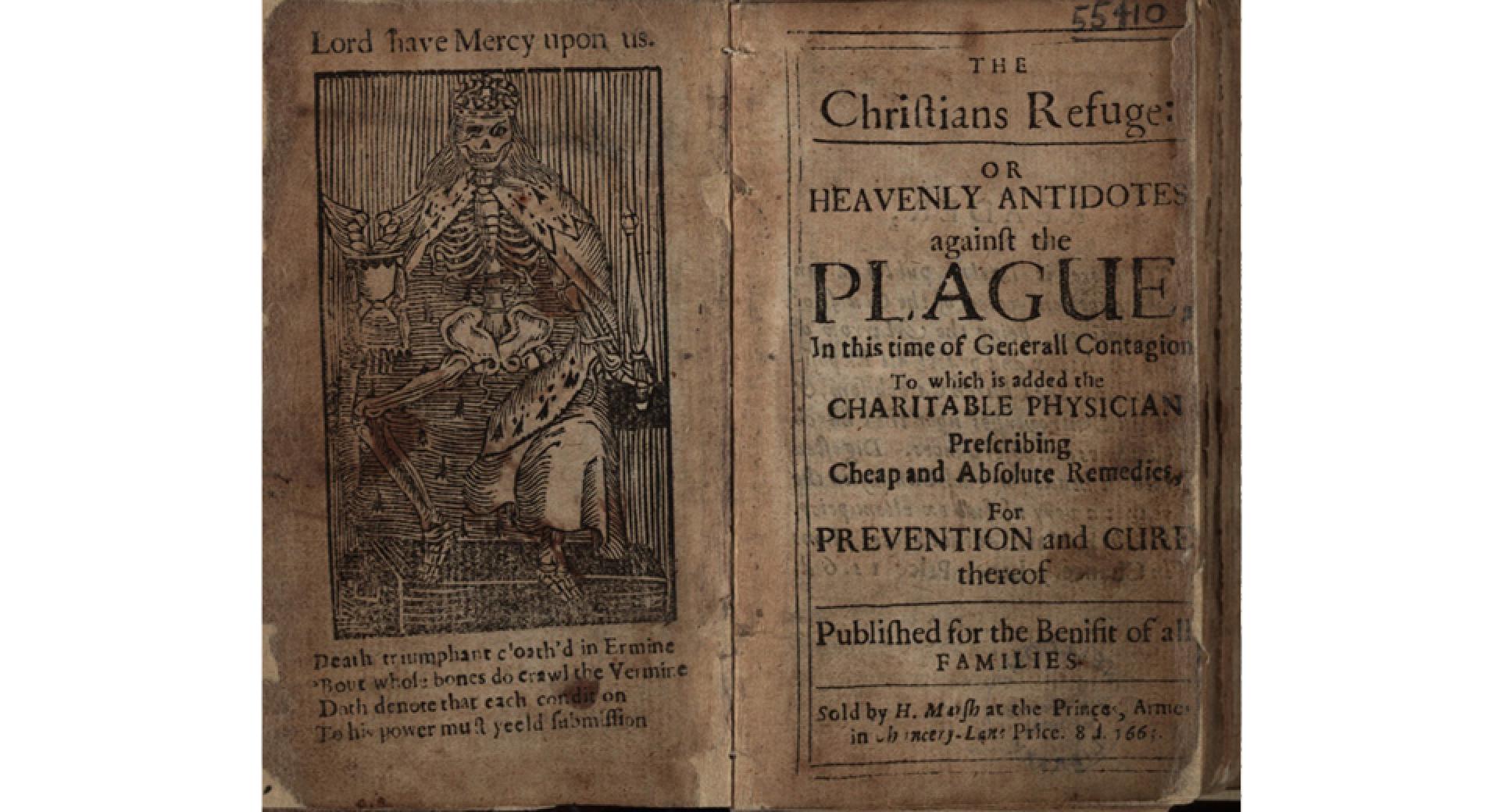

Two natural disasters, The Great Plague of 1665, and the Great Fire of London in 1666, occurred in his lifetime and he described both in vivid detail. He lived in a period of great social change, when the puritan morality of the Commonwealth gave way to the more licentious and spirited society ofthe Restoration. He goes into delicious, and disturbingly honest, detail about his home life, his affairs, his ever-increasing wealth, some of it obtained dubiously, and the passions of the court.

He witnessed it all and wrote about it in wonderfully evocative language. Here he is in November 1660, describing a meeting with a friend who reminded him of his attendance at the beheading of Charles I when Pepys was just a 15 year-old boy.

‘He did remember that I was a great roundhead when I was a boy, and I was much afeared that he would have remembered the words that I said the day the King was beheaded that, were I to preach upon him, my text should be “The memory of the wicked shall rot”. ( November 1, 1660)

He remained in London through the plague year of 1665, writing, ‘I did in Drury-lane see two or three houses marked with a red cross upon the doors, and “Lord have mercy upon us” writ there – which was a sad sight to me’. (June 7, 1665

Later, he seems more depressed as the plague has taken hold of London. Here is his entry for October 16 1665:

‘I walked to the Tower. But Lord, how empty the streets are, and melancholy, so many poor sick people in the streets, full of sores, and so many sad stories overheard as I walk, everybody talking of this dead, and that man sick, and so many in this place, and so manyin that. And they tell me that in Westminster there is never a physician, and but one apothecary left, all being dead — but that there are great hopes of a great decrease this week: God send it.’

The following year, during the Great Fire of London, he was at the centre of the efforts to save the city from the flames, reporting on the events like Dan Rather;

‘Some of our mayds sitting up late last night to get things ready against our feast to-day, Jane called us up about three in the morning, to tell us of a great fire they saw in the City. So I rose and slipped on my nightgowne, and went to her window, and thought it to be on the backside of Marke-lane at the farthest; but, being unused to such fires as followed, I thought it far enough off; and so went to bed again and to sleep. About seven rose again to dress myself, and there looked out at the window, and saw the fire not so much as it was and further off. So to my closett to set things to rights after yesterday’s cleaning. By and by Jane comes and tells me that she hears that above 300 houses have been burned down to-night by the fire we saw, and that it is now burning down all Fish-street, by London Bridge.’ (September 2nd, 1666)

And later, he’s examining the fire from a better vantage point. ‘I up to the top of Barking steeple, and there saw the saddest sight of desolation that I ever saw; every where great fires, oyle-cellars, and brimstone, and other things burning. I became afeard to stay there long, and therefore down again as fast as I could, the fire being spread as far as I could see it; and to Sir W. Pen’s, and there eat a piece of cold meat, having eaten nothing since Sunday, but the remains of Sunday’s dinner.’ (September 4th 1666)

He’s very good on the details. Pepys records burying his parmesan cheese and his wine in a pit in the garden, scorched pigeons falling from the skies, a burnt cat pulled alive from a chimney, the price of a loaf (two pence), glass melted and buckled by the heat and people burning their feet on the scorched ground.

Like the great reporter and observer Pepys is, he puts us in the middle of the action, hearing, smelling, seeing, feeling and touching the events for ourselves.

It is that ability to combine the personal with the political which makes Pepys unique. He can go from describing what he had to eat for breakfast to the latest machinations amongst the mistresses of the King in a couple of sentences. All with a trade mark wit and power of observation.

‘I now took them to Westminster Abbey and there did show them all the tombs very finely, having one with us alone (there being other company this day to see the tombs, it being Shrove Tuesday); and here we did see, by perticular favour, the body of Queen Katherine of Valois, and had her upper part of her body in my hands. And I did kiss her mouth, reflecting upon it that I did kiss a Queen, and that this was my birthday, 36 years old, that I did first kiss a Queen.’ (Feb 29th 1669).

There is so much to love and admire in the Pepys Diaries. If you are in the UK, there is a wonderful exhibition on until March at Greenwich featuring the man and his times.

Finally, here is his entry for this day 350 years ago on February 23rd 1666, when he seems happy with the world.

‘So I supped, and was merry at home all the evening, and the rather it being my birthday, 33 years, for which God be praised that I am in so good a condition of healthe and estate, and every thing else as I am, beyond expectation, in all. So she to Mrs. Turner’s to lie, and we to bed. Mightily pleased to find myself in condition to have these people come about me and to be able to entertain them, and have the pleasure of their qualities, than which no man can have more in the world.’

A wonderful epitaph for the man and his life.